|

Our Torah portion for this week concerns various social and civil laws of ancient Israel called "mishpatim." The Hebrew word mishpatim (מִשְׁפָּטִים) means "rules" or "judgments," and is derived from a root meaning "to judge" (i.e., shafat, שָׁפַט). The LORD is called Ha-Shofet kol ha'aretz (הֲשׁפֵט כָּל־הָאָרֶץ) -- the "Judge of all the earth" who loves justice (Gen. 18:25, 37:28, Psalm 50:6, 94:2). We are therefore commanded to pursue righteousness through the exercise of right judgment: tzedek, tzedek tirdof (צֶדֶק צֶדֶק תִּרְדּף): "Justice, Justice you shall pursue" (Deut. 16:20). In other words, the LORD God expects us to make upright decisions based on the revelation of moral truth given in the Scriptures (Prov. 31:9, John 7:24).

The great commentator Rashi noted that this portion of Torah continues the earlier account of the Sinai revelation. The parashah begins: וְאֵלֶּה הַמִּשְׁפָּטִים אֲשֶׁר תָּשִׂים לִפְנֵיהֶם - "Now these are the judgments (ha'mishpatim) that you shall set before them" (Exod. 21:1). Rashi notes that the term ve'eileh (וְאֵלֶּה, "and these are...") is always used to add or continue the preceding text. In other words, the connecting Vav (ו) links what is being said with what went before. The sages infer, then, that the mishpatim, were written to elaborate the teaching (תּוֹרָה) first given in the Ten Commandments.

|

Parashat Mishpatim is sometimes called Sefer HaBrit (סֵפֶר הַבְּרִית), "the Book of the Covenant," because it lists various social laws that Moses wrote down (Exod. 24:7). It is therefore a "subset" of the Torah -- a separate scroll -- that elaborated on the terms of the covenant initially made at Mount Sinai (i.e., the giving of the Ten Commandments). After it was written, Moses built an altar at the foot of Mount Sinai with twelve pillars (one for each tribe of Israel), and ordered sacrifices to the LORD to be made. He then took the sacrificial blood from the offerings, threw half upon the altar and read the covenant to the people. The people ratified the covenant with the words: כּל אֲשֶׁר־דִּבֶּר יהוה נַעֲשֶׂה וְנִשְׁמָע / kol asher diber Adonai na'aseh v'nishma ("all that the LORD says we will do and obey" (Exod. 24:7). Upon hearing their ratification, Moses took the other half of the sacrificial blood and threw it on the people saying, "Behold the blood of the covenant (דַּם־הַבְּרִית) that the LORD has made with you in accordance with all these words" (Exod. 24:8).

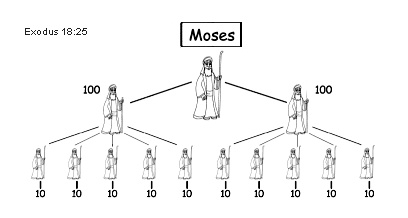

Recall that Moses appointed judges (shoftim, from the same root as mishpatim) to help interpret and apply the Ten Commandments for the people (Exod. 18:13-26). Later he anticipated the need for these judges to be appointed in every city in the Promised Land to decide civil, domestic, and even religious controversies (see Deut. 16:18, 17:8-11). This is the origin of the Bet Din (בֵּית דִּן) and later of the "Great Sanhedrin," both of which were based on the fundamental idea of Oral Law. Over time the legal reasoning of the shoftim became codified in "case law" as formal explanations of halakhah (i.e., the legally binding aspects of the Oral Law). In traditional Judaism, this view of Torah may be regarded as a line of transmission from God to Moses (in the Torah), through the prophets, through the men of the Great Assembly, the Talmudic Rabbis and the Talmudic literature, down to several medieval codes and their responsa (Avot 1:1). In Jewish thinking, then, "Torah" means not only the writings of Moses preserved in the Torah scrolls, but also the collective corpus (and therefore consensus) of Jewish rabbinic law, custom and tradition over the centuries.

|

As mentioned above, the very concept of mishpatim implies that God expects us to make wise decisions based on truth (Prov. 31:9, John 7:24). Not everything is "spelled out" in the writings of the Scriptures, and therefore we must use clear thinking to make valid inferences about the meaning of the original texts. We are commanded to "rightly divide" (ὀρθοτομέω, lit. "cut straight") the "word of truth" (דְּבַר הָאֱמֶת, see 2 Tim. 2:15). Therefore, in order to avoid confusion regarding the relationship between the Torah of Moses (תּוֹרַת משֶׁה) and the Torah of Yeshua (תּוֹרַת הַמָּשִׁיחַ), we must keep in mind that Torah is always a function of the underlying covenant (בְּרִית, "cut") of which it is part. Failure to make this distinction leads to exegetical errors and invalid doctrines.

Followers of the Messiah are no longer slaves -- not to a religious "system" nor to the letter of the law itself (2 Cor. 3:3; John 15:15). Blindly following religious traditions and rules does not honor the LORD and is actually a form of slave mentality (Gal. 4:25). Those who miss the point of the Torah are likened to those who "strain out a gnat" while swallowing a camel (Matt. 23:24). We do not worship Jewish traditions or the ideals of Jewishness, but rather the Living Word of God....

Why, then, was the lawcode given? To function as a "tutor" or "guardian" (παιδαγωγός) to lead us to the School of the Messiah (Gal. 3:19-25). Note that the Greek word used here ("paidagogos") referred to a trusted servant who would supervise the life and morals of boys belonging to the upper class. Before arriving at the age of manhood, boys were not allowed to leave their house without being escorted by their "paidagogos." Followers of the Messiah are admonished not to revert to childish thinking but to understand matters maturely (1 Cor. 13:11, 14:20, Heb. 5:12-14). We are now led by the Spirit of God as God's sons and are therefore no longer "subject" to religious regulations (δόγμα) that command us to "touch not, taste not, handle not." We are now called to seek those things that are above, where the Messiah reigns from on high (Col. 2:20-3:1). "Therefore do not be foolish, but understand what the will of the Lord is" (Eph. 5:17). Yeshua came to bear witness to the truth: "Everyone who is of the truth listens to my voice" (John 18:37). The truth sets us free to become co-heirs with the Messiah in the Kingdom of God (Rom. 8:17, Titus 3:7, John 8:32). If we love the Messiah, we will honor His covenant and His Torah (2 Cor. 10:5).

Most of us, I am afraid, don't really want to be free... It's so much easier for us to justify ourselves as pleasing to God on the basis of some litany of rules we are keeping (i.e., church attendance, 'quiet times' with God, etc.) or some ritual acts that we are performing (i.e., 'communion,' 'liturgy," 'Shabbat observance,' and so on). We feel more comfortable in a group, as part of a crowd. We do not want to live as truly free individuals before the LORD because this implies that we (alone) are responsible for our lives. But genuine freedom only comes through individual and personal faith (אֱמוּנָה). We must inwardly trust that we have direct access to the Throne of Grace (כִּסֵּא הֶחָסֶד) and are accepted by God as His own beloved child (Heb. 4:16, Rom. 8:15). God has made us "graceful" (χαριτόω) in the beloved (Eph. 1:6). This is the first step, and all the rest will take care of itself if we really do business there...

But aren't Christians supposed to be nonjudgmental people? "Judge not that you be not judged," said Yeshua. Not exactly. Yeshua also warned us not to judge by appearances, but "judge with righteous judgment" (John 7:24), that is, with the eye of love... In the context in which he spoke (i.e., teaching the crowd during the festival of Sukkot in Jerusalem), Yeshua justified healing someone on the Sabbath day as an example of understanding the "weightier matters" of the Law. Yeshua's appeal to the crowd was to think things through -- and then come to a decision. He was not advocating that people "turn off their brains" and accept the authority of the religious establishment of his day, quite the contrary.

Let's return to the idea of the mishpatim (judgments) given in the Sefer Habrit of Moses. The underlying impetus for these social rules was to help Israel (collectively) live a sanctified life before the LORD. In other words, the mishpatim were connected with ideas of mussar (rebuke and correction) for the good of the community. This is enshrined in the maxim: שֶׁכּל יִשְׂרָאֵל עֲרֵבִים זֶה בָּזֶה / she-kol Yisrael arevim zeh ba-zeh: "All Israel is responsible for one another." Each Jew is responsible for his fellow Jew. Holiness was not simply a matter of personal purity but involved the entire community. We share one another's burdens - and that includes one another's sins. We are our "brother's keeper." (Note that this idea of mutual responsibility is expressed in the New Testament as well, using the metaphor of the relationship between the whole and its parts: "For just as the body is one and has many parts, and all the parts of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with the Messiah (1 Cor. 12:12-27, Col. 3:15)). The "Law of Messiah" is to bear one another's burdens (Gal. 6:2, James 5:16, etc.).

We were created by God to be social beings, part of a great community of love called the "family of God." God our Father is therefore profoundly interested in our relationships with others -- so much so that if these relationships are damaged, our relationship with Him will suffer (see Matt. 5:23-24, 6:15, 18:35; Mark 11:25-26, Eph. 4:32, Col. 3:13). Of course "we all stumble in many ways" and "offenses (σκάνδαλον) will come" (James 3:2, Matt. 18:7), but we must be forgiving and repair the breaches in our relationships (James 5:16). Forgiveness means asking of ourselves what we are asking of God. The same is true of love. When Yeshua taught us to "forgive us as we forgive," He taught that our forgiveness (of others) is our forgiveness (of God). Conversely, demanding perfection from others means appealing to God to be the judge of our lives -- and therefore means coming under self-examination.... This is the "do unto others" rule of life, the "like for like" measure of love, and the "karma" that attaches to moral reality (Gal. 6:7-8). We simply cannot have it both ways. We cannot claim divine mercy for ourselves while desiring retribution for others. The law of God must be used lawfully (1 Tim. 1:5-11).

Indeed, Yeshua extended the "like-for-like" nature of love (with its implicit appeal to self-interest) by commanding us to (literally) love our enemies (Matt. 5:44, Luke 6:27). Most of us find rationalizations to excuse ourselves from this duty, of course, and we are only too glad to accept the propaganda of the world that wars are patriotic, that vengeance is "just," that people who are different from us are to be regarded with suspicion, and so on. Yeshua, however, says: "Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven" (Matt. 5:44-45). Love is more important than even truth, or better, love is the ground or foundation of the truth... Love is truth, in other words, at least from the perspective of Heaven. God doesn't call out people to become "professors" as much as He calls people to become lovers. Love is willing to embrace the wrong in others in redemptive hope. If we find ourselves unwilling to extend such grace, perhaps it's because we are struggling to accept it as our own....

There are moral obligations between ourselves and others (mitzvot bein Adam l'chavero) as well as moral obligations between ourselves and God (mitzvot bein Adam lamakom). These obligations are really two sides of the same coin, with the common term being the duty to love (or to care). Followers of Yeshua have a profound obligation to love and care for one another (John 13:34, 15:12,17, Rom. 13:8; 1 Thess. 4:9; 1 Pet. 1:22, 1 John 3:11, etc.). After all, in this world the only tangible way we can express our love for God is by extending love to other people (James 2:15-17, 1 John 3:17, 4:20). Indeed, our obligation to love and care for others can even preempt our outward duty to love God Himself. For example, what good is it to "tithe mint and cumin" and yet neglect the needs of those who are suffering (Matt. 23:23)? Tragically, the idea of "loving" or "serving" God can even be used as a pretext for rejecting those with whom we might disagree... What else explains religious hatred, hidebound denominational prejudices, and other forms of sanctimonious humbug at work in the various world religions of today? Even in so-called Christian churches we see this sort of bigotry at work. As Yeshua forewarned: "the hour is coming when whoever kills you will think he is offering service to God" (John 16:2). Sadly this sometimes applies even to those who claim to love and worship the Prince of Peace (שַׂר־שָׁלוֹם). The world's religious zealots are routinely trying to "do God a favor" by hating and even killing others... This is the "Jihad-version" of religiosity - a terrible sickness of spirit. In light of the redemptive love and grace of God, can there really be anything more perverse than this?

The phrase "respect precedes Torah" (דרך ארץ קדמה לתורה) means that before we can even begin to study the Torah and to serve God, we must respect ourselves and others. We must first of all care! When the Torah commands us: וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָּמוֹךָ / "love your neighbor as yourself" (Lev. 19:18, Matt. 22:36-40, Mark 12:33, Rom. 13:9-10, Gal. 5:14, etc.), the underlying assumption is a healthy sense of self-love that comes from accepting that you are created in the likeness of God Himself. Being indifferent toward others is really a form of self-hatred, a kind of spiritual suicide. As it is written, "You shall not hate your brother in your heart, but you shall reason frankly with your neighbor, lest you incur sin because of him" (Lev. 19:17). Loving others means caring enough to confront them when they sin to avoid complicity with their sin. Apathy, indifference, and so on, is the opposite of brotherly love (Heb. 3:13). The sages advise that when you feel compelled to reprove your brother or sister, you must reprove yourself at the same time. Know that you have a share in his or her sin.... Humility is the keyword.

Love is intended to be reciprocal, even if it is unconditionally given. In other words, love can only exist when it is shared with others. This is the "law of love" (תּוֹרַת הָאַהֲבָה). Some of the mystics have said that when two people sincerely love one another, the Holy One reigns between them. This is alluded to by the Hebrew word for love (i.e., ahavah, אהבה), the gematria of which is thirteen, but when shared with another it is multiplied: 13 x 2 = 26 - the same value for the Name of the LORD (יהוה). The commandment, "You shall love your neighbor as yourself" thus awakens in the other the same kind of love for you -- and the result will be a "double love" -- the very love of the LORD: "Where two or more are gathered in my Name, there I AM in the midst of them" (Matt. 18:20). May God fill you with His Holy Spirit and will help you walk in the truth of love...

הָאהֵב אֶת־חֲבֵרוֹ קִיֵּם אֶת־הַתּוֹרָה

hah·oh·hev · et - cha·ve·roh · kee·yeim · et · ha·toh·rah

ἀγαπῶν τὸν ἕτερον νόμον πεπλήρωκεν

"Whoever loves his fellow human being

has fulfilled Torah" (Rom. 13:8).

Download Study Card

|