|

Recently someone wrote to ask my opinion of whether women (or Messianic non-Jews in general) were permitted to wear "tzitzit," that is, the fringes or tassels tied to the corners of the tallit gadol (traditional Jewish prayer shawl). Since Jewish law forbids the use of tzitzit for both women and non-Jews, this person asked me to weigh in on the subject...

This question (once again) raises the subject of whether a follower of the Messiah should adhere to the law code of Moses. Sadly, many well-meaning Messianic believers seem to confuse the idea of Torah (ū¬ų╝ūĢų╣ū©ųĖūö) with that of covenant (ūæų╝ų░ū©ų┤ūÖū¬) and therefore fail to "rightly divide" (ßĮĆŽü╬Ė╬┐Žä╬┐╬╝ßĮ│Žē, lit. "cut straight") the "word of truth" (ūōų╝ų░ūæųĘū© ūöųĖūÉų▒ū×ųČū¬, see 2 Tim. 2:15). As I've said over and over, the failure to make this crucial distinction invariably leads to doctrinal confusion and strife within an assembly of people.

If you claim to be a follower (i.e., talmid, or "student") of Yeshua then you are to receive, study, and accept the yoke of the "Torah of the Messiah" (ū¬ų╝ūĢų╣ū©ųĘū¬ ūöųĘū×ų╝ųĖū®ūüų┤ūÖūŚųĘ). In other words, you will submit to His authority as your Master by walking in His love (2 John 1:9, 1 Tim. 6:3-6; John 15:12; 1 John 3:23, etc.). The law of Moses (ū¬ų╝ūĢų╣ū©ųĘū¬ ū×ū®ūüųČūö) was intended to function as a "propaedeutic" (ŽĆ╬▒╬╣╬┤╬▒╬│Žē╬│ßĮ╣Žé) or "tutor" for apprehending the Messiah's greater instruction (Gal. 3:19-25). Note that the Greek word used here ("paidagogos") referred to a trusted servant who would supervise the life and morals of boys belonging to the upper class. Before arriving at the age of manhood, boys were not allowed to leave their house without being escorted by their "paidagogos." Followers of the Messiah are admonished not to revert to childish thinking but to understand matters maturely (1 Cor. 13:11, 14:20, Heb. 5:12-14). Even the most zealous among the Jewish people could not bear the strain of the yoke of the Torah of Moses, as Peter testified (Acts 15:9-10). We are now led by the Spirit of God as God's sons and are therefore no longer "subject" to religious regulations (╬┤ßĮ╣╬│╬╝╬▒) that command us to "touch not, taste not, handle not." We are now called to seek those things that are above, where the Messiah reigns from on high (Col. 2:20-3:1).

Followers of Yeshua have a "better covenant based on better promises" (Heb. 8:6), and the lawcode was meant to foreshadow a greater Substance that was promised by the prophets (2 Cor. 3:18, 4:6). Even the Mishkan (and Temple) were "shadows" (Žā╬║╬╣╬▒ßĮĘ) of the greater priesthood of Yeshua, who alone combined the divine offices of Israel's King and High Priest (Heb. 10; Zech. 3:8, 6:12, etc.).

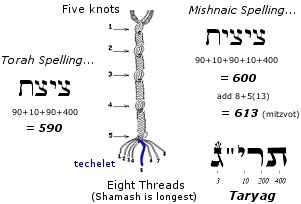

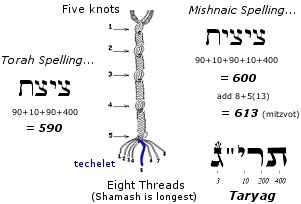

The test of practical doctrine (such as whether or not to wear a Tallit, whether to recite Kiddush on Shabbat, etc.) is whether the action gives glory to Yeshua or not (1 Cor. 10:31). The role of the Holy Spirit (ū©ūĢų╝ūŚųĘ ūöųĘū¦ų╝ūōųČū®ūü) is to glorify the Messiah (John 16:14), and anything that detracts from this end is decidely not given from Heaven (John 5:23). We are at liberty to wear tzitzit AND are are at liberty to refrain from wearing them. "Let every one be fully persuaded in his own mind" (Rom. 14:5). We talk a lot about the "old" covenant and the "new" covenant, but what about the "now" covenant? The real question is the heart's motive and secret desires -- right now.

Personally I believe that whatever helps us to sanctify the LORD in our hearts and to express our love for Yeshua is a good thing.... On the other hand, it is crucial to understand that wearing tzitzit, lighting candles, and so on, are merely visual aids, or a "making visible the invisible," of what is ultimately true within in our hearts... They are not "shibboleths" or recipes to gain access to the LORD, since Yeshua alone is our High Priest and Intercessor and it is by means of His zechut (merit) that can draw near to the Father. Even less are tzitzit to be regarded in terms of "ritual magic," or as an amulet that supposedly possess some sort of mystical power....

Understanding the radical freedom that Yeshua gives comes from the profound awareness that we are - and ever shall be - utterly insufficient to please God in our own merits, and therefore we cast ourselves upon the mercy and grace of God given through the life of Messiah. Struggling with various modes and means of pleasing God through any form of service or ritual observance might be indicative that there is a deeper struggle concerning the acceptance of our own inner bankruptcy and need for deliverance.

|